The Save gas station on the west side of Gary, Indiana, wants customers to know that they can pay for their groceries with food stamps. When I pulled into the parking lot last week, the first thing I saw was a blinking neon sign that read EBT for electronic benefits transfer, the prepaid cards used by food-stamp recipients. Inside, I spotted coolers packed with drinks, and shelves and shelves of snacks. But a black-and-white sign on the cashier window had a warning: As of January 1, soda and candy can no longer be purchased with food stamps.

Indiana is one of five states—along with Iowa, Nebraska, Utah, and West Virginia—that has begun banning the purchase of certain unhealthy treats with food stamps, which is formally known as the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program. They have all been spurred into action by Robert F. Kennedy Jr., who has made these bans a priority of his tenure as health secretary. “There’s no nutrition in these products,” Kennedy said in June, celebrating the policy at an event with Indiana’s governor. “We shouldn’t be paying for them with taxpayer money.” Later this year, 13 more states will start implementing similar changes to their food-stamp programs. The Trump administration is pushing more states to follow suit by giving those that do preferential access to a $50 billion pool of money meant to improve rural health care across the country.

In the two weeks since the first bans went into effect, the results have been messy. My trip to Indiana and conversations with officials in other states have suggested that the policies are disorienting, and the implementation has been inconsistent. Nowhere was that clearer than at the 20/20 Food Mart a few blocks away from Gary’s airport. When I entered the store, I was immediately confronted with a multi-shelf display of treats—chocolate-chip cookies, honey buns, double-chocolate muffins—all displayed next to handwritten signs that read Special: EBT item. This seemed like a mistake, but it wasn’t. Baked goods like these can still be bought with food stamps because Indiana’s new policy bans only the purchase of soft drinks and candy.

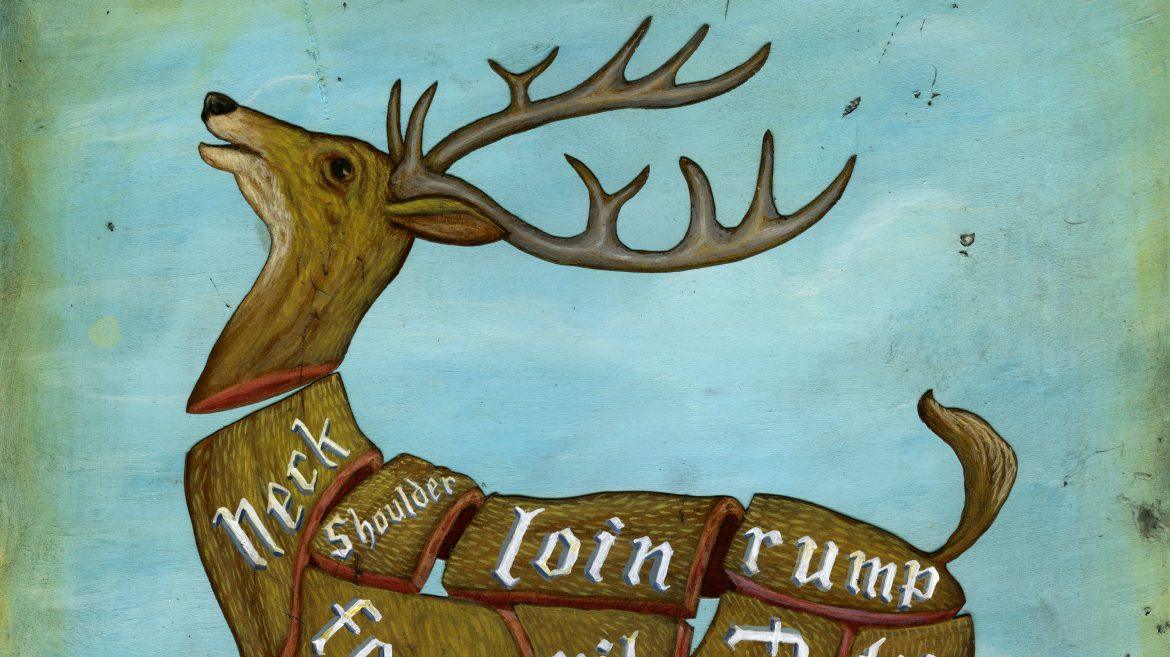

Baked treats aren’t alone in occupying this regulatory gray area. Protein bars can still be purchased with food stamps, even if they have the same amount of sugar as a chocolate candy bar; chocolate-covered nuts, however, cannot. Sugary, canned coffee is also okay, so long as it has milk. (The policy says that soft drinks do “not include beverages that contain milk or milk products.”) Iowa’s ban has a similar loophole. What can be purchased with SNAP is based on how food is taxed in the state, which has led to some perplexing scenarios. Iowans can use their EBT cards to buy a slice of cake—but not a fruit cup that comes with a spoon.

[Read: Republicans are right about soda]

What all of this shows is that banning junk food is more complicated than it seems. Previously, SNAP recipients could use their cards to purchase pretty much anything to eat besides hot food or alcohol. States are in the unenviable position of defining broad categories such as soda and candy and then figuring out whether any of the snacks you might find in a store are eligible for food stamps. On a public call with retailers, Indiana officials recently denied a request for a comprehensive list of the products that can and cannot be purchased, citing that they would need to wade through “tens of thousands, if not hundreds of thousands of products.” The inventory, the officials added, would quickly go out of date because of new product launches. However, the state has “a general list of commonly asked-about items,” a spokesperson for the Indiana Family and Social Services Administration told me.

Much of the burden for determining which items can or can’t be purchased falls to the best judgment of store clerks. In Indiana, retailers are responsible for knowing that the state defines soft drinks as “nonalcoholic beverages that contain natural or artificial sweeteners,” meaning that Gatorade is also banned. In spite of the challenges, stores appear to be implementing the changes fairly well, but some products are bound to fall through the cracks: At one gas station in Gary, I was incorrectly told that I could buy an energy drink with food stamps. At another, I was told I couldn’t buy bottled coffee, even though it had milk.

This puts food-stamp recipients in a tough situation. At a Family Dollar in Gary, the soda refrigerators were still decorated with SNAP stickers, implying that the drinks inside could be purchased. The store had also printed out signs warning about the new changes, but they were posted around boxes of cereal, which are still SNAP-eligible. At another Family Dollar in town, the signs were posted on a display of blankets, which never could be purchased with SNAP. Critics of these restrictions worry that such confusion could drive people away from the food-stamp program. “Singling out people who receive SNAP, policing their shopping carts, and delaying their purchases at the register would inevitably decrease participation rates,” states a recent essay in Georgetown University’s Journal on Poverty Law & Policy.

Before moving forward with these policies, Indiana, Iowa, and other states had to get approval from the Department of Agriculture, which oversees the food-stamp program. In previous administrations, the agency blocked attempts to crack down on junk food precisely because of the problems the states are now facing. In 2011, USDA, which oversees SNAP, denied New York City’s request to implement a soda ban, warning that “the proposal lacks a clear and practical means to determine product eligibility,” which would create problems for stores.

Much of the confusion that currently plagues these bans will likely subside over the next few months, as retailers and SNAP participants gain familiarity with the rules. (USDA has also announced that it will give retailers a 90-day grace period before it begins testing compliance.) Even with the messiness, the policies could still be a net positive for the health outcomes of food-stamp recipients, Alyssa Moran, a nutrition-policy researcher at the University of Pennsylvania, told me. According to the USDA’s own research, sugary drinks are among the most popular food-stamp purchases.

That said, the full effects of these bans will not be known until they are assessed by researchers, likely years from now. The USDA approved these bans as temporary pilots with the aim of evaluating exactly what cracking down on junk food would mean for public health. But according to Cindy Long, who in September stepped down as deputy undersecretary for food, nutrition, and consumer services at USDA plans for evaluation so far have been thin. Nebraska’s proposed evaluation plan, for example, appears to be just one paragraph, which says that the state will evaluate SNAP participants’ spending habits quarterly and work with retailers to “determine the reduction in purchases of soda and energy drinks.”

Nebraska could still bulk up its research plan in the coming months—the plan states an intention to work with USDA “to determine the appropriate evaluation measures”—but the fact that it was approved by USDA with such little specificity marks a shift in how the administration is approaching these requests. New York’s proposed approach included a telephone survey, an evaluation of retail-sales data, and surveys of SNAP participants leaving grocery stores. Even then, an agency official wrote that “the proposed evaluation design is not adequate to provide sufficient assurance of credible, meaningful results.”

Exactly how USDA will now assess whether one state’s policy worked better than another’s remains to be seen. A spokesperson did not answer my questions about whether the government would evaluate the policies itself. “USDA continues to work with states by providing technical assistance to support these efforts,” the spokesperson told me.