It was a travesty—two travesties, actually, separate but inextricably linked. In May 1953, Edmund Hillary and Tenzing Norgay became the first people to reach the summit of Mount Everest, a challenge that had killed more than a dozen people in the preceding decades and that scientists had once declared impossible. The catch: They breathed canisters of pure oxygen, an aid that the Everest pioneer George Mallory—one of those who died on the mountain—had once dismissed as “a damnable heresy.”

A month later, a young British medical trainee named Roger Bannister just missed running the first sub-four-minute mile, another long-standing barrier sometimes dubbed “Everest on the track.” But he did it in a race where his training partner let himself be lapped in order to pace Bannister all the way to the finish line, violating rules about fair play due to the advantages of pacing. Bannister’s American rival, Wes Santee, was unimpressed. “Maybe I could run a four-minute mile behind one of my father’s ranch horses,” he said, “if that’s what you want.”

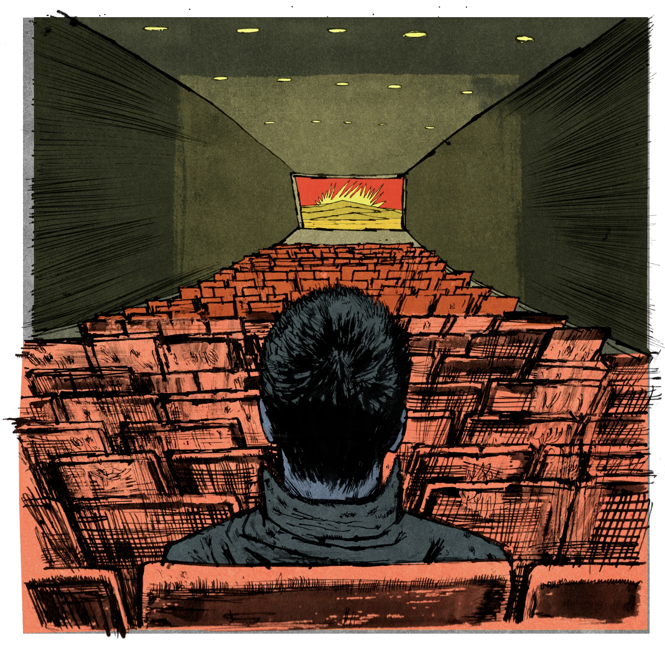

Funny how history repeats itself. Fast-forward to a couple of weeks ago: A controversy erupted in the world of mountaineering, when four British climbers summited Everest just five days after jetting to Nepal from the United Kingdom. To skip the usual weeks or months spent gradually adjusting to high altitude, they paid a reported $153,000 each for a bespoke protocol that included inhaling xenon gas to help them adjust more rapidly. Meanwhile, on the track, Kenya’s three-time Olympic champion, Faith Kipyegon, is preparing for a carefully choreographed, Nike-sponsored attempt to become the first woman to run a mile in under four minutes. It’s slated for June 26 in Paris and will almost certainly violate the same pacing rules that Bannister’s run did.

Both initiatives are, by any measure, remarkable feats of human ingenuity and endurance. They’re also making people very angry.

The xenon-fueled expedition was organized by an Austrian guide named Lukas Furtenbach, who is known for his tech-focused approach to expeditions. He has previously had clients sleep in altitude tents at home for weeks to pre-acclimatize them to the thin mountain air. What made the new ascent different is that, in addition to sleeping in altitude tents, the four British climbers visited a clinic in Germany where they inhaled xenon gas, whose oxygen-boosting potential has been rumored for years. The World Anti-Doping Agency banned xenon in 2014 after allegations that Russian athletes used it for that year’s Winter Olympics. But subsequent studies on its athletic effects have produced mixed results. Other research in animals has hinted at the possibility that it could offer protection from potentially fatal forms of altitude illness, which can occur when climbers ascend too rapidly. For now, the strongest evidence that it helps high-altitude mountaineers comes from Furtenbach’s own self-experimentation over the past few years.

When news of Furtenbach’s plans emerged earlier this year, the International Climbing and Mountaineering Federation’s medical commission put out a statement arguing that xenon probably doesn’t work and could be dangerous because of its sedative effects. Other critics have pointed out that shorter expeditions mean less paying work for the Sherpa guides in the region. But these criticisms can feel like post hoc justifications for the fact that many mountaineers simply have a gut-level aversion to what seems like a shortcut to the summit. Their objection isn’t to xenon itself but to the idea of making Everest easier.

That’s the same problem many runners have with Kipyegon’s sub-four-minute-mile attempt. Women have made extraordinary progress in the event since Diane Leather notched the first sub-five in 1954, but under conventional racing conditions, no one expects a sub-four anytime soon. Kipyegon is the fastest female miler in history: Her current world record, set in 2023, is 4:07.64, which leaves her more than 50 yards behind four-minute pace—an enormous deficit to overcome in a sport where, at the professional level, progress is measured in fractions of a second. Nike has promised “a holistic system of support that optimizes every aspect of her attempt,” including “footwear, apparel, aerodynamics, physiology and mind science,” but hasn’t revealed any details of what that support might look like. That means critics—and there are many—don’t yet have any specific innovation to object to; they just have the tautological sense that any intervention capable of instantly making a miler 7.7 seconds faster must by definition be unfair. (I reached out to Nike for further specifics about the attempt, but the company declined to comment.)

It’s a safe bet that new shoes will be involved. Kipyegon’s effort, dubbed Breaking4 by Nike, is a sequel to the company’s Breaking2 marathon in 2017, in which Kipyegon’s fellow Kenyan Eliud Kipchoge came within 25 seconds of breaking two hours at a time when the official world record was 2:02:57. Kipchoge’s feat was made possible in part by a new type of running shoe featuring a stiff carbon-fiber plate embedded in a thick and bouncy foam midsole, an innovation that has since revolutionized the sport. But the reason his time didn’t count as a world record was that, like Bannister, he had a squad of pacers who rotated in and out to block the wind for him all the way to the finish line. That’s also likely to be a key for Kipyegon. In fact, scientists published an analysis earlier this year suggesting that a similar drafting approach would be enough to take Kipyegon all the way from 4:07 to 3:59 without any other aids.

Bannister’s paced-time trial in 1953 was ruled ineligible for records because, per the British Amateur Athletic Board, it wasn’t “a bona fide competition according to the rules.” Still, the effort had served its purpose. “Only two painful seconds now separated me from the four-minute mile,” Bannister later wrote, “and I was certain that I could cut down the time.” Sure enough, less than a year later, Bannister entered the history books with a record-legal 3:59.4. Similarly, Kipchoge went on to break two hours in another exhibition race in 2019, and Nike’s official line is that it hopes that feat will pave the way for a record-legal sub-two in the future. (It’s certainly getting closer: The world record now stands at 2:00:35.) In 1978, a quarter century after Hillary and Norgay’s historic ascent, Reinhold Messner and Peter Habeler climbed Everest without supplemental oxygen.

One view of innovation in sports, advanced by the bioethicist Thomas Murray, is that people’s perceptions are shaped by how new ideas and techniques are introduced. The status quo always seems reasonable: Of course we play tennis with graphite rackets rather than wooden ones, use the head-first Fosbury flop to clear high-jump bars, and climb mountains with the slightly stretchable kernmantle ropes developed in the 1950s. But many of these same innovations seem more troublesome during the transition periods, especially if only some people have access to them.

When Bannister finally broke the four-minute barrier, he was once again paced by his training partners, but only for about the first three-quarters of the race. This form of pacing remained highly controversial, but because none of the pacemakers had deliberately allowed himself to be lapped, the record was allowed to stand. These days, such pacing is so routine that there are runners who make a living doing nothing but pacing races for others, always dropping out before the finish. The full-race pacing that Kipyegon will likely use in Breaking4 remains verboten; the slightly different pacing that leads runners almost all the way through the race but forces them to run the last lap alone is simply business as usual. Oxygen in a can is good; xenon in a can is bad. These are subtle distinctions.

Sports are, in at least some respects, a zero-sum game: When one person wins a race or sets a record, it unavoidably means that someone else doesn’t. Even at the recreational level, if everyone decides to run marathons in carbon-plated shoes that make them five minutes faster, the standards needed to qualify for the Boston Marathon get five minutes faster. “Once an effective technology gets adopted in a sport, it becomes tyrannical,” Murray told me several years ago, when I was writing about athletes experimenting with electric brain stimulation. “You have to use it.” In the ’50s, a version of that rationale seemed to help the British expedition that included Hillary and Norgay overcome the long-standing objections of British climbers to using oxygen—the French had an Everest expedition planned for 1954 and the Swiss for 1955, and both were expected to use oxygen.

Less clear, though, is why this rationale should apply to the modern world of recreational mountaineering in which Furtenbach operates. What does anyone—other than perhaps the climbers themselves, if you think journeys trump destinations—lose when people huff xenon in order to check Everest off their list with maximal efficiency? Maybe they’re making the mountain more crowded, but you could also argue that they’re making it less crowded by getting up and down more quickly. And it’s hard to imagine that Furtenbach’s critics are truly lying awake at night worrying about the long-term health of his clients.

Something else is going on here, and I’d venture that it has to do with human psychology. A Dutch economist named Adriaan Kalwij has a theory that much of modern life is shaped by people’s somewhat pathological tendency to view everything as a competition. “Both by nature and through institutional design, competitions are an integral part of human lives,” Kalwij writes, “from college entrance exams and scholarship applications to jobs, promotions, contracts, and awards.” The same ethos seems to color the way we see dating, leisure travel, hobbies, and so on: There’s no escape from the zero-sum dichotomy of winners and losers.

Kalwij’s smoking gun is a phenomenon that sociologists call the “SES-health gradient,” which refers to the disparities in health between people of high and low socioeconomic status. Despite the rise of welfare supports such as pensions and health care, the SES-health gradient has been widening around the world—even, Kalwij has found, among Olympic athletes. There used to be no difference in longevity among Dutch Olympians based on their occupation. But among the most recent cohort, born between 1920 and 1947, athletes in high-SES jobs, such as lawyers, tend to outlive athletes in low-SES jobs by an average of 11 years. As Kalwij interprets it, making an Olympic team is a life-defining win, but getting stuck in a poorly paying dead-end job is a loss that begets an endless series of other losses: driving a beater, living in a lousy apartment, flying economy. These losses have cumulative psychological and physiological consequences.

Some things in life really are competitions, of course. Track and field is one of them, and so we should police attempts to bend its rules with vigilance. Other things, such as being guided up Everest, are not—or at least they shouldn’t be. The people who seem most upset about the idea of rich bros crushing Everest in a week are those who have climbed it in six or eight or 12 weeks, whose place in the cosmic pecking order has been downgraded by an infinitesimal notch. But I, too, was annoyed when I read about it, despite the fact that I’ve never strapped on a crampon. Their win, in some convoluted way, felt like my loss.

Another detail in Kalwij’s research sticks in my mind. Among American Olympians, silver medalists tend to die a few years earlier than either gold or bronze medalists. Kalwij theorizes that these results, too, are related to people’s outlook. Gold medalists are thrilled to win, and bronze medalists are thrilled to make the podium; silver medalists see themselves as “the No. 1 loser,” as Jerry Seinfeld once put it. With that in mind, I’ve tried to reframe my attitude about the xenon controversy. Let the annual Everest frenzy continue, with or without xenon, and let its allure continue to draw the most hard-edged and deep-pocketed summit baggers. Meanwhile, leave the other, lesser-known mountains for the rest of us to enjoy in tranquility. I’d call that a win.